The Lily of St. Mark’s by Steve Carey (“C” Press, 1978)—31 pages, side-stapled mimeograph edition of 250 copies. Printed at The Poetry Project. Cover art and interior portrait by George Schneeman.

In Alice Notley’s essay “Steve,” written as a lecture given June 19, 1998 at Naropa (digitized here) and collected in her book Coming After: Essays on Poetry, Notley describes first meeting Steve Carey in her apartment at 101 St. Mark’s Place: “He has a deep beautiful voice, from deep in a big chest. It’s the voice (I will soon find out) that all his poems ride, they’re conceived for that sound, fluid, changeable, playing…it will make up words for us, contribute permanently to our vocabulary.” “[H]is sensibility is responsive to every delicacy in words,” she writes, and this precisely the musical flexibility—mouthy jostle (to coin a Carey-esque phrase)—that permeate the poems in The Lily of St. Mark’s. I’ve coveted a copy of this book for a long time and just recently was able to get one. The bold intricacy of Schneeman’s playing card-style cover, even the title itself, which is such a quintessential late-1970s, New York School gesture—a wry and lyric gendered play that incorporates the hyper-localized geography of the Second Generation—make this book an irresistible object. It’s also the penultimate publication of Ted Berrigan’s “C” Press—which he revived in 1978 to publish Carey’s book and, finally, Elio Schneeman’s In February I Think. As Notley descirbes, “This title is after the song ‘The Lily of the West’ (sung by Joan Baez, and also and not very well by Dylan) suggesting Steve’s Westernness (he loves whitewall tires and smog and Ed Ruscha photos) and his pallor and esthetic purity) which Ted sometimes chides him for, as in Ted’s line ‘Absolute quality tells absolutely nothing’).” Carey’s recent move to New York City from the West Coast—and the quick dissolution of his marriage, as Notley describes in the above essay—maps over the song’s narrative. The allusion is as witty as it is sentimental, a warm mixture of feeling and intelligence that continues to be one of the little-discussed joys of poets such as Carey, Berrigan, Notley, and other “Second Generation” New York School writers.

A few years ago I wrote a short review of The Selected Poems of Steve Carey, edited by Edmund Berrigan (Subpress, 2009), which I’ve included at the end of this post. Everything there holds true for The Lily of St. Mark’s, but many of the poems in this book that don’t appear in the Selected are worth highlighting for their raucous, idiosyncratic swerves of phrase. This is also a way of saying that I’d like to create a record of the need for more of Carey’s poems to be easily available, and that a Collected Poems of Steve Carey would be a celebrated publication for poets and scholars interested in writers like Carey whose work has not been widely read or written about. Notley’s endorsement should be all we need. Elinor Nauen’s narrative of Carey’s last day alive—originally published in The Poetry Project Newsletter in Oct./Nov. 1989—is a strong portrait of Carey’s humor, devotions, and love. “There’ll be marigolds in my next poem,” he tells Nauen. He’d die of a heart attack the next day.

Carey’s sense of a line’s ability to whimsically bend, light up, usher in, and fizz is one of the core delights of his work. He is a genius of generating that odd-ball variation in a phrase that makes the most familiar language an unstable chemical substance. He rivals Ashbery and Koch as a list-making poet. His verbs are miraculous. His miniature collages of newly minted phrases are scenes of dramatic wit and care. His humor carries the effect of a TV-set constantly shifting between channels—voices, tones, contexts gently running together into poems that are neither sets of non sequiturs nor fixed narratives. He can make language into science fiction. And all throughout are his friends and his love for them. Carey’s work looms with spirited presence. It’s voice-y and thrilled. Its shine is its wit. It gets weird in any light. Check the poem “Wasi-Wasi” for examples of nearly all of the above.

Below is a quick inventory of incredible lines from The Lily of St. Mark’s:

“About Poetry (II)” for Keith Abbott: “But dizzy hailing worthies / I am light — I think I’m light — and toss / these options aft.”

“Folk Song”: “I have no lethal heavens, roaring plently.”; “Your plans, and sign surprise, and rout / Deep breathing, beef your weaving lean, / And cry, ‘Light! Die light! Die light!’”

“‘The Pills Aren’t Working’”: “Out—hamming fury—as I do”

“The Islands”: “To what you got to kneel beside / Female dusts will burgeon / Clutter and bind these hard hands / Where their song shall keep”

“Poem (Middle Distance)”: “creeping dream deprivation / roaring bores”

“Poem From a Line by Philip Whalen”: “Bless the all but silent sleep / conveying fabulous muddles of the kug / pictured to serve.”

“Slo-Mo” for Ted Berrigan: “as I (banking in a slow drop) / watch a dawn bump up at the far line.”

“Dread”: “Of the pave, / of the pave, / ‘Now there’s some music / I can drive to!’ // A penalty flag falls to the ground. // Slowly, I produce the knife!”

“About Poetry” for Bill Berkson: “There is herald all in tone.”; “Talking in our sleep… / The books grow bigger / And bigger. Fine books.”

***

From left to right: Alice Notley, Harris Schiff, Ted Berrigan, and Steve Carey at 101 St. Mark’s Place apartment. Courtesy of Stuart A. Rose Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library, Emory University.

Review of The Selected Poems of Steve Carey, edited by Edmund Berrigan (Subpress, 2009)—originally published in NOÖ Journal #17:

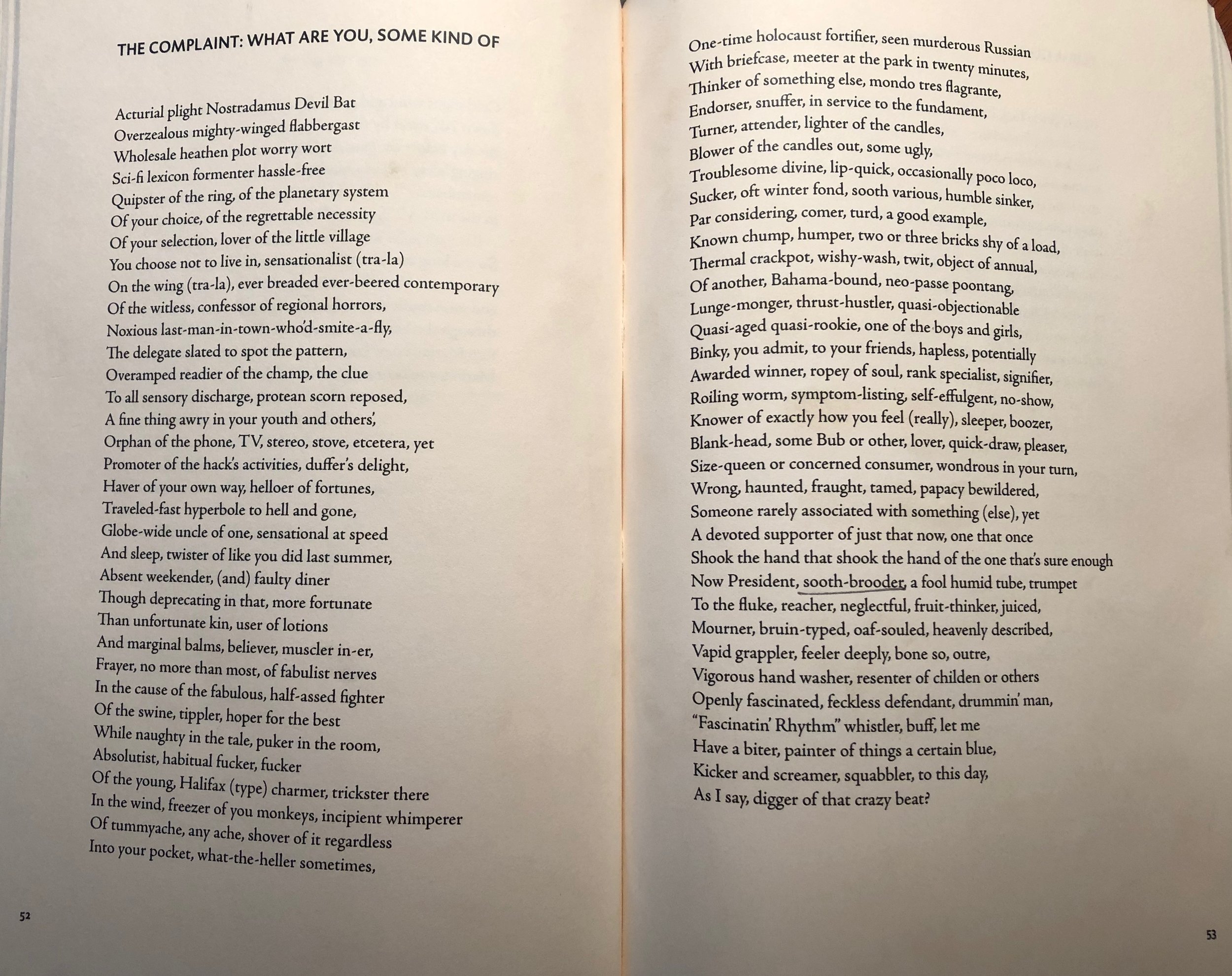

Steve Carey’s poetry is a jubilant assemblage of crystal phrases and sets, an ongoing practice in the delight and incongruity that emerges in and between uncommon lines, our living ghosts and singing voices. Carey, who died at age 43 in 1989, is associated with the fierce, joyous, trembling, visionary sounds of the Second Generation New York school poets, and his work shows an intimate overlap with the poetry of Ted Berrigan, Alice Notley, Bill Berkson, Philip Whalen, and others around the Poetry Project and Naropa in the 1970s and early 80s. But what’s a generation or a school do for readers who find Carey for the first time in this Selected, the first gathering of his work in over 25 years? I came to Carey’s work through a dedicated reading of Berrigan’s poetry, a microlineage that allowed me to trace a common devotion in language and sound rather than a canonical tradition. And in these poems, which are so funny and attentive, carried so pleasurably by the weird light of a phrase like “You’re swacked” or the miraculous turning music in “Sweatless in my place / Dear, dear gate,” we swerve so much and so gently in each line that we’re made into beginners, starting again along with Carey to be readers of ourselves and our shared musics. It’s a good thing to be a beginner in these poems—it leaves us radically open, without jealousy or anxiety, dreaming. Carey is describing his own practice, and telling us a secret about music, when he writes, “In each a rhythmic adjustment is made // ‘Everyone is haunted / Watch the water.’” Both meditative and fervently busy, we’re riding each phrase to its textured next of kin. One of the most terrific things about Carey’s poems is his use of punctuation, that language within language that (re)organizes so much of a poem’s music. In poems like “Julia” and “Joe Hill,” Carey’s use of parentheses, hyphens, and quotation marks make for a lush braiding that subnarrates the movement of thinking, line by line, like Dickinson, Howe, or Notley. He, like them, is “[t]urning her face to her sources,” living in a jeweled, far, unprecious sound. Anyone familiar with the New York School will be at home in Carey’s Selected, but these poems are a long drift past categorization. Edmund Berrigan’s selection of poems, from more on-site lyric arrangements to long open field poems to Carey’s incredible list works, like the unbelievably pleasurable “The Complaint: What Am I, Some Kind Of,” gives us the most generous shapeliness for reading Carey’s work. A true “sooth-brooder,” a wayward “Thinker of something else,” Carey’s voice is still here for new readers, critically joyous, crystalline, and tender. Tra-la, tra-la.

Full PDF of The Lily of St. Mark’s: click here

Full PDF of 20 Poems: click here

Tom Carey’s Papers, the archive of Steve Carey’s brother, recently became available at Yale’s Beinecke Library.

from The Selected Poems of Steve Carey